Researchers in France have discovered that, though a tattoo may be forever, the skin cells that carry the tattoo pigment are not. Instead, the researchers say, the cells can pass on the pigment to new cells when they die. The study, which will be published 2018, March, in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, suggests ways to improve the ability of laser surgery to remove unwanted tattoos.

For many years, tattoos were thought to work by staining fibroblast cells in the dermal layer of the skin. More recently, however, researchers have suggested (https://www.jci.org/articles/view/JCI32282) that macrophages—specialized immune cells that reside in the dermis—are attracted to the wound inflicted by the tattoo needle and gobble up the tattoo pigment just as they would normally engulf an invading pathogen or piece of a dying cell. In either case, it is assumed that the pigment-carrying cell lives forever, allowing the tattoo to be more or less permanent.

A team of researchers led by Sandrine Henri and Bernard Malissen of the Centre d’Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy developed a genetically engineered mouse that allowed them to kill the macrophages that reside in the dermis and certain other tissues. Over the following few weeks, these cells are replaced by new macrophages derived from precursor cells known as monocytes.

The researchers found that dermal macrophages were the only cell type to take up pigment when they tattooed the mice’s tails. Yet the tattoos’ appearance did not change when the macrophages were killed off. The team determined that the dead macrophages release the pigment into their surroundings where, over the following weeks, it is taken up by new, monocyte-derived macrophages before it can disperse.

©Baranska et coll., 2018

Caption: Because tattoo pigment can be recaptured by new macrophages, a tattoo appears the same before (left) and after (right) dermal macrophages are killed.

This cycle of pigment capture, release, and re-capture occurs continuously in tattooed skin, even when macrophages aren’t killed off in a single burst. The researchers transferred a piece of tattooed skin from one mouse to another and found that, after six weeks, most of the pigment-carrying macrophages were derived from the recipient, rather than the donor, animal.

“We think that, when tattoo pigment-laden macrophages die during the course of adult life, neighboring macrophages recapture the released pigments and insure in a dynamic manner the stable appearance and long-term persistence of tattoos,” Sandrine Henri explains.

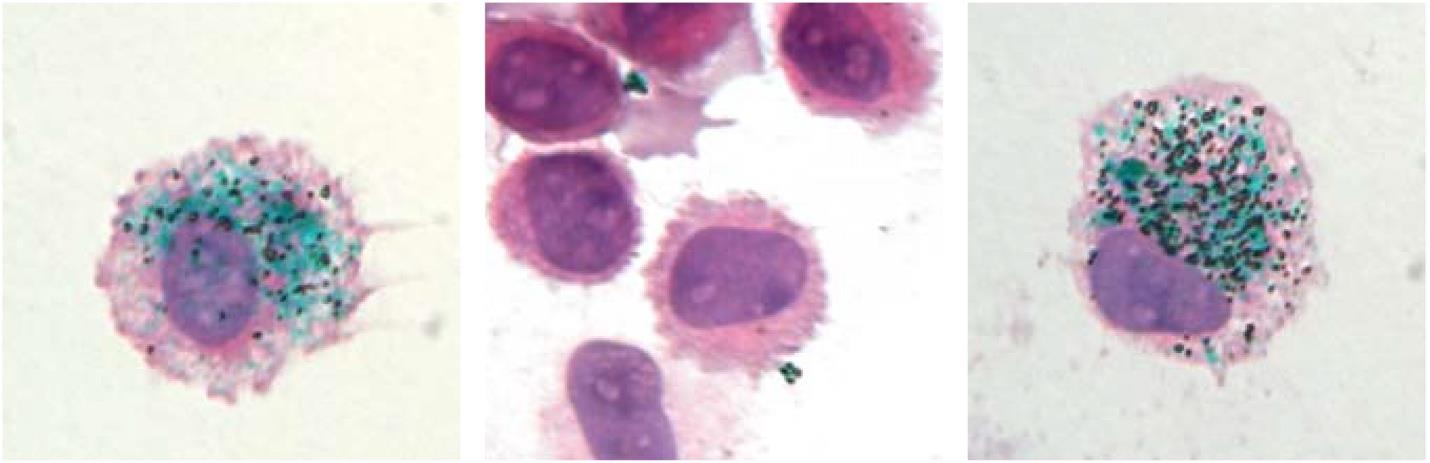

©Baranska et coll., 2018

Caption: Green tattoo pigment is taken up by dermal macrophages (left). The pigment is released when these cells are killed (center) but, 90 days later, is taken back up into new macrophages that have replaced the old ones (right).

Tattoos can be removed by laser pulses that cause skin cells to die and release their pigment, which can then be transported away from the skin and into the body’s lymphatic system.

“Tattoo removal can be likely improved by combining laser surgery with the transient ablation of the macrophages present in the tattoo area,” says Bernard Malissen. “As a result, the fragmented pigment particles generated using laser pulses will not be immediately recaptured, a condition increasing the probability of having them drained away via the lymphatic vessels.”

Sources

Unveiling skin macrophage dynamics explains both tattoo persistence and strenuous removal

Anna Baranska1, Alaa Shawket1*, Mabel Jouve3*, Myriam Baratin1*, Camille Malosse1, Odessa Voluzan1, Thien‑Phong Vu Manh1, Frédéric Fiore2, Marc Bajénoff1, Philippe Benaroch4, Marc Dalod1, Marie Malissen1,2, Sandrine Henri1**, and Bernard Malissen1,2**

1 Centre d’Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, Aix Marseille Université, INS ERM, CNRS UMR, Marseille, France;

2 Centre d’Immunophénomique, Aix Marseille Université, INS ERM, CNRS, Marseille, France;

3 UMR3215, Institut Curie, Paris, France; 4Institut Curie, PSL Research University, INS ERM U932, Paris, France.

Journal of Experimental Medicine

Contact chercheur

Sandrine Henri

Inserm Reseracher

Unité 1104 Centre d’immunologie de Marseille – Luminy (CIML)

« Genetic dissection of the function of T cells and dendritic cells » Team

06 81 84 00 62

henri@ciml.univ-mrs.fr

Bernard Malissen

Unité Inserm 1104 Centre d’immunologie de Marseille – Luminy (CIML)

« Genetic dissection of the function of T cells and dendritic cells » Team

Unité de service Inserm 12 Centre d’immunophenomique (CIPHE)

bernardm@ciml.univ-mrs.fr

Contact presse

presse@inserm.fr

Accéder à la salle de l'Inserm